Hi, Friend.

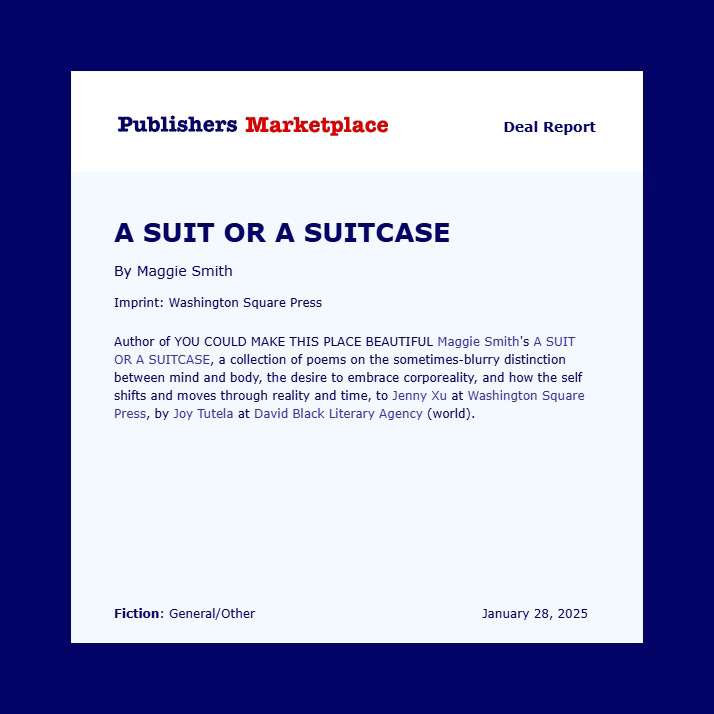

On Valentine’s Day I escaped to a coffee shop for a couple of hours, and one of the things I worked on was my new book of poems, A Suit or a Suitcase. The collection will be out in March 2026 (official announcement below), but we’re already in the first round of copyedits!

It’s a very different book from my last two collections of poems—much less about motherhood, for one thing—but it’s also exciting to read through the poems again and see how they speak back to and from every other poem I’ve written. Art is like this, I think: one extended conversation that will last our whole lives, if we’re lucky. Today I’ve annotated the title poem, “A Suit or a Suitcase.”

Thanks to Kaveh Akbar for giving this poem such an incredible first home in The Nation. Here’s how the poem appears there.

A Suit or a Suitcase

You ask what I’ll miss about this life.

Everything but cruelty, I think.

But you want one specific thing,

so here—I’ll miss my body. I’ll miss

its companionship, how it’s traveled

with me, never leaving me—& by me,

I mean my mind. My soul? My self?

I don’t know what to call it, & besides,

my body hasn’t traveled with me.

I’ve traveled inside it. Do I wear it

or does it carry me? Is the body a suit

or a suitcase? Bear with me here.

I’ve always thought of who I am

as being concentrated in my head & chest,

as if there’s a waterline at my ribcage

& contrary to their density, thoughts

& feelings stay afloat. You asked

what I’ll miss about this life, & now

I’m way down a rabbit hole, wondering

if I could breathe deeply enough

to redistribute my mind more evenly

throughout my body—or soul rather

than mind? Or self? I don’t even know

what to call the me of me. I imagine

filling my body completely, filling it,

every inch, to the skin. Shh. Listen.

Ideas are whispering in my wrists

& all along the slopes of my calves.

When you lay your head on my thigh,

when you kiss the backs of my knees, listen.

I’m trying to tell you what I’ll miss—

everything but cruelty, but mostly this.

I don’t know about you, but when I read a poem or an essay, I want to know about how it was made. What was the spark? Why did the writer make those specific choices? How was the finished piece different from what they might have expected at the outset? When I launched this newsletter, I knew that one of the things I wanted to do was try to answer those questions about pieces of my own.

In the handwritten annotation below I’ve noted some of the craft choices I’ve made related to word choice, sound play, line breaks, and the overall movement of the poem, but I also confess to the framework of the poem being fudged a bit. No one asked me what I would miss about this life; it was a question I wondered about to myself: What will I long to hold onto, aside from the people I love, when it’s time for me to go?

My answer surprised me: my body. Or, rather, the way it’s allowed me to move in the world and have sensory experiences. Seeing clouds. Smelling salt air. Kissing and being kissed (etcetera, etcetera, ahem). This answer inspired me to create a “you” in the poem that the speaker could address and bounce these ideas off of. Many of the poems in A Suit or a Suitcase show me grappling with these body/mind (or mind/heart, or body/soul) questions.

Looking at this annotation, I first notice the form: couplets, or two-line stanzas, which slow the poem down and allow each stanza to be cushioned in white space. Imagine if the stanza breaks were removed and the poem were just one unbroken chunk of text. Imagine if the stanzas were sturdy quatrains (four-line stanzas) instead of these lighter, airier couplets. Imagine if the poem were typed up as a prose poem, looking like a paragraph instead of verse.

You see my point. When you’re choosing the shape of your poem—line length, stanza length—you’re considering these potential effects. For “A Suit or a Suitcase,” which follows the speaker’s train of thought (“Bear with me here”) to some unexpected places, I felt that slowing the poem down would help the reader track these moves.

There is a fair amount of sound play in this poem—alliteration, assonance, and consonance—but I think the most notable music is in the final couplet, which rhymes.

I’m trying to tell you what I’ll miss—

everything but cruelty, but mostly this.

The end rhyme emphasizes this last sentence, and—at least to my ear—stitches the poem shut. I think the sense of closure also comes from the stanza being closed rather than open; the sentence is completely contained in the final couplet, not carried over from the previous stanza. (Note that the last three couplets are all closed in this way: They begin with a new sentence and end with punctuation, which gives a sense of finality. If you go back further, you’ll see that most of the stanzas are enjambed, with sentences carrying over from one couplet to the next and often across several stanzas.)

You might think of end-stopped lines (lines that end with any type of punctation) as places where the brakes are being pumped, with terminal punctuation (like a period or question mark) being a hard stop. These “hard stops” fall on lines 1, 2, 7, 9, and 12, and then they are heavy at the end in lines 26, 28, 30, and 32. “Bear with me here” and “Listen” are both commands to the reader, and the periods after these commands fall not only at the ends of the lines but at the ends of the stanzas, before a longer pause inside that white space. This makes the commands more emphatic. The reader sits with them a beat longer.

On the other hand, enjambment allows for suspense—a kind of floating—at the ends of lines, so that the reader needs to keep reading to know where the sentence is going. In any poem with varied line endings, there’s a tension between the closure of end-stopped lines and the openness (and ongoingness) of enjambed lines, and to me that tension feels right in a poem with a speaker that grapples, thinks aloud, and second-guesses herself.

I hope that looking at these cause-and-effect choices not only helps you think about how you might approach your own poems, but also how you read, talk about, or teach poetry: What decisions did the author make, and what effects do those decisions have on your experience of the piece? If you have questions for me, please ask in the comments.

As you can probably imagine, I talk at length about craft choices in Dear Writer: Pep Talks & Practical Advice for the Creative Life, which comes out April 1. If you haven’t preordered a copy yet, I hope you’ll take a moment to do that from your local indie, Bookshop.org, or wherever you buy your books. There’s a special preorder giveaway, too, where you can upload proof of purchase to register for a craft zoom with me this spring, once book tour is over and I’m back at my desk for a stretch!

I expect my next post to be a pep talk, because I need one and I imagine you could use one, too. Life is…a lot right now, and the cruelty this poem references is on constant display. Please take good care.

With gratitude,

Maggie

I remember this poem from “You Could Make This Place Beautiful” and loved the sheer quirkiness and thought provoking nature of it. I also love the choices that you talk about and the conversational tone you take in this particular piece. It feels like we are a part of the poem and the conversation, making it feel warm and inviting.

Thanks so much, Maggie. I was curious why you chose ampersands versus “and.” Was it to tie the two words as a unit?