Behind-the-Scenes Look: "Document"

Annotation & Author’s Note

Hi, Friend.

I’m sure this comes as no surprise, but when I read something by another writer—a poem, an essay, a book—I’m immediately curious about its backstory. What was the inspiration behind it? How did the writer arrive at those specific craft choices? How was the finished piece different from what they might have expected at the outset? When I launched this newsletter, I knew that one of the things I wanted to do was pull back the curtain as a poet and offer some behind-the-scenes looks.

Today I’m sharing an handwritten annotation of “Document,” a poem from my new book, A Suit or a Suitcase, which comes out in March. (Preorders are a love language!) The poem is also one of two new poems of mine in the gorgeous January/February 2026 issue of Poetry. Here’s how it looks in the magazine:

I wrote “Document” last spring at a cabin in the woods in southern Ohio. I call it my happy place, and at least part of every book I’ve ever published has been written there. I remember sitting in a chair by the fire, looking out the window, and noticing sunlight coming down through the leaves. (The word in Japanese is komorebi, meaning “sunlight filtering through trees.”) I’d been thinking—and writing—a lot about memory and the way the self is revised over time. These are themes that come up again and again in A Suit or a Suitcase.

I’ve been going to that cabin, or one neighboring it, for 22 years. I’ve been watching sunlight (or rain, or snow, or high winds) through those trees for 22 years. It’s a repeated experience and yet a new experience every single time. Even if the trees and the view are exactly the same, the light is not, and the season is not, and the time of day is not, and I am not. The perspective changes because the viewer changes.

I sometimes joke with writer friends about the hubris of saving a draft and calling it final. Because inevitably it’s revised again, and the file needs to be renamed accordingly. Maybe you can relate to this as a writer who has named a file “final_revised” or “final_final_2.” Maybe you can relate to this as a human being who feels yourself changing—being revised by the passage of time and by your own experiences—even if it’s in small ways that may not be noticeable to others. Maybe both ring true for you. Our writing changes. So do we.

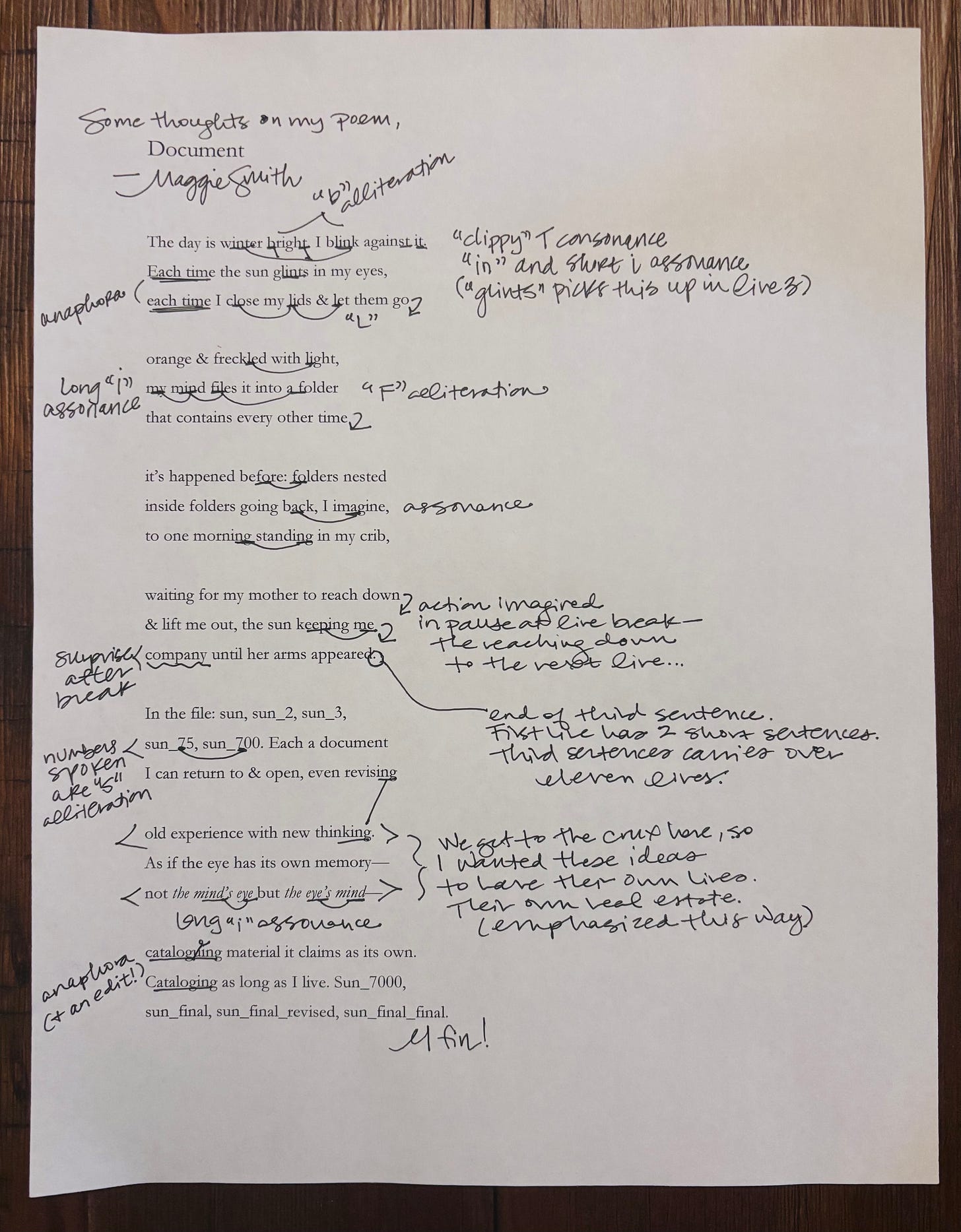

In the handwritten annotation of “Document” below, I’ve noted some of the craft choices I made related to word choice, sound play, line breaks, and the overall movement of the poem.

Looking at the annotation, I first notice the form: tercets, or three-line stanzas. I tend toward a shorter stanza (couplets and tercets especially) because I often like a slower pace; the white space between each stanza slows the reader down and gives more opportunities for smaller exits and entrances aside from the grand entrance of the first line and the final exit of the last line. I can see from reading the first stanza that my instinct was to break at “let them go” for suspense and tension, and to use the extra white space o/f the stanza break to carry that suspense a bit longer. The first tercet then became a kind of template for the rest of the poem. It set the pattern.

There is a fair amount of sound play in this poem. In the opening line I hear what I’m describing as “clippy” consonance: light, staccato sounds, “T” and short “I” especially. I’ve noted alliteration, assonance, and consonance throughout, including the numbers, which are primarily “S” numbers to be alliterative with sun. I’ve also pointed out anaphora, which appears at the beginning of lines in the first stanza (“each time”) and again in the final stanza (“cataloging”).

Line breaks throughout the poem play on suspense and, I hope, sometimes subvert the reader’s expectations. For example, in stanza four, the line break at “keeping me” could lead a lot of different places, and I think “company” comes as a surprise. That surprise would be lost if we kept “keeping me company” together on one line. (This is something I’d recommend playing with in your own poems: testing out breaking lines at various words to see which ones generate the most interest and charge.)

Generally speaking, enjambment allows for suspense—a kind of floating—at the ends of lines, so that the reader needs to keep reading to know where the sentence is going. In any poem with varied line endings, there’s a tension between the closure of end-stopped lines and the openness (and ongoingness) of enjambed lines.

Reading the poem again, I think the sense of closure also comes from the slowing down of the pacing in the last two stanzas, in which every line is end-stopped with some kind of punctuation: comma, em dash, or period. End-stopped lines (lines that end with any type of punctation) are places where the brakes are being pumped, with terminal punctuation (like a period) being a hard stop. The end of the poem feels very closed and final to me, because the word final itself is repeated so many times, and is doubled in the last instance.

I remember finishing this poem at the cabin and knowing that even though it was very new, it belonged in A Suit or a Suitcase. Sometimes that happens—a poem comes quickly, but it makes a case for itself. I’m curious if that’s happened to you! If so, or if you have any questions or comments for me, I hope you’ll share.

What else? I’ll have some travel news to share with you before too long! We’ve finalized tour cities for A Suit or a Suitcase, so I’ll post the locations and dates as soon as I can. In the meantime, the event links for Brooklyn (with Amber Tamblyn) and Columbus (with Marcus Jackson) are already live, and you can register now. I’d love to see you!

Take good care—

Maggie

I have started a series based on the journal I have been keeping for 35 years. Most installments are based on the current day but some dip back into the past and I slot them into the series where I think they fit, kind of like how you feel as if a poem belongs in a certain place such as a future book.

As a prose writer, I'm struck by your "keeping company" as opposed to "keeping me company" comment. Because I realize I do that in my prose writing because I write the way I talk. I want the writing to speak like me. But then I find myself correcting for that because "that's not the way grammar works" and I feel like I have to submit to proper grammar when I'm also submitting to sentences and paragraphs. Maybe I won't anymore, though.