Craft Tip

Stanza & Pacing

I don’t remember when I first learned that stanza is Italian for “room,” but I know it changed the way I thought about the organization and movement of a poem. A stanza in a poem is like a paragraph in prose—a structural unit within a greater whole. A room in the house.

To push the metaphor further: some received forms come with a blueprint, so you know roughly what the house will look like once you build it. (You know a sestina when you see it!) But with a free-verse poem, the structure is up for grabs. You have to ask yourself: What stanzas, what “rooms,” best serve this particular poem?

You might lean toward stanzas that are irregular in length; like rooms in a house, some might be larger—and contain more—than others. Or you might choose uniform stanzas, like couplets (two lines each), tercets (three lines), quatrains (four lines), and so on.

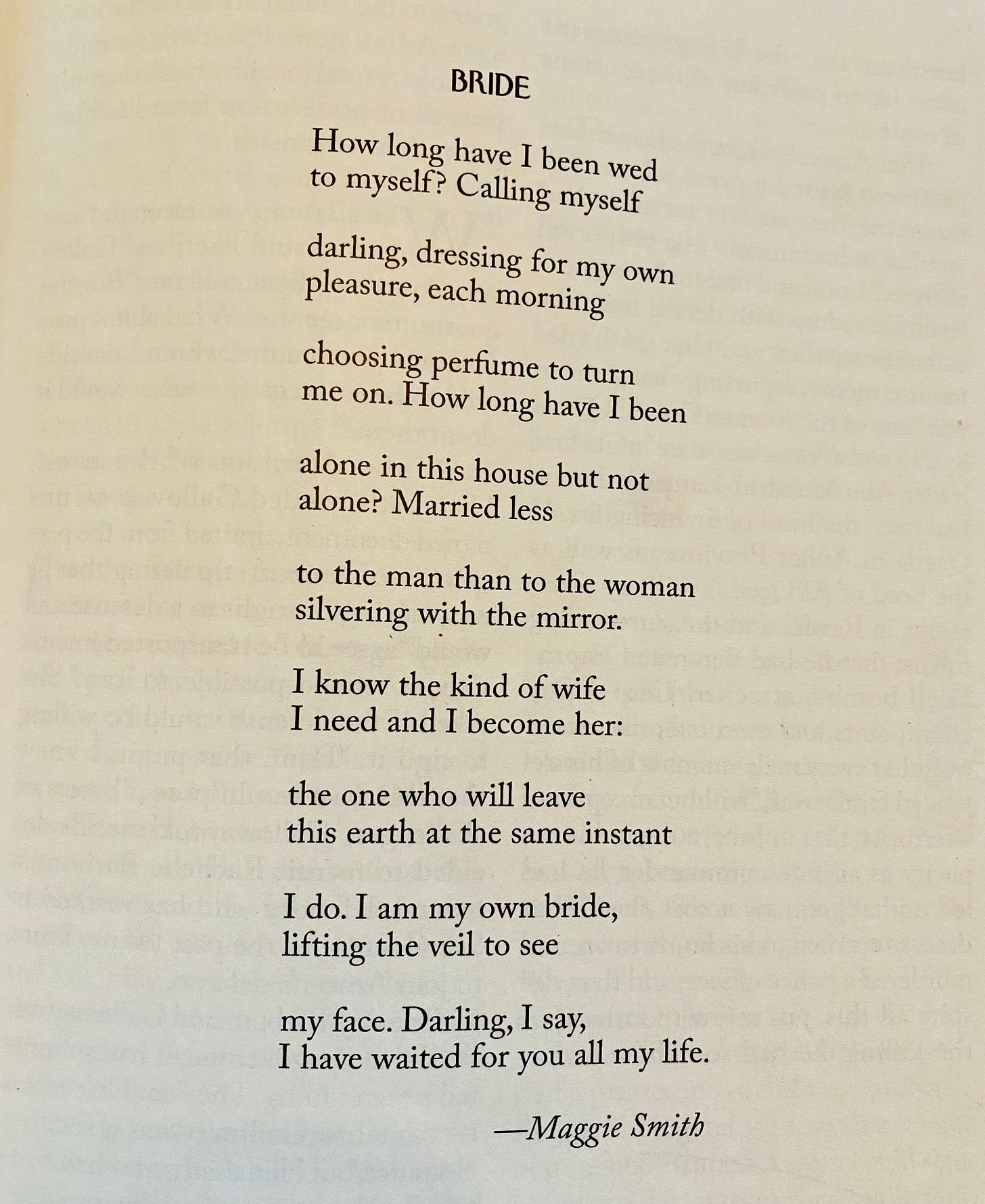

Sometimes the stanza is an opportunity to enact or embody something in the poem’s content. I landed on couplets for “Bride,” for example, because two-line stanzas felt thematically right to me. It’s a love poem, after all—a poem about a couple. The twist is that the “marriage” that is most essential in the poem is the one between the poem’s speaker and herself.

I have a soft spot for unrhymed couplets. I like the padding of white space around them, so each stanza is like a piece of art hung on a gallery wall. White space is literal “breathing room” on the page, and it slows a poem down. Shorter stanzas in a poem = more white space between stanzas on the page = more time for the reader to savor each line.

To slow a poem down, build in more white space by shortening the stanza length. You can also shorten the line length to slow the reader down.

To pick up the pace in a poem, do the opposite: lengthen the stanzas by removing white space. You can also speed up the reader’s momentum by lengthening the lines.

As I draft a poem, I often decide on the line length and the grouping of lines I prefer for the opening stanza, and then I use that line and stanza length as a template for the rest of the poem. If I prefer the opening to be a quatrain, for example, I’ll naturally try quatrains for the whole poem and see if that might work. Sometimes it does, but not always. Other times I might find that irregular stanzas work best, or I might end up collapsing the whole poem into a single stanza to speed it along.

As you draft, take each poem on a case-by-case basis. What stanzas, what “rooms,” best serve this particular poem? Just because couplets worked for your last poem doesn’t mean that stanza length is the best choice for your next poem. Experiment with various options, reading aloud as you go, to see what appeals to your eye and ear.

Happy writing—

Maggie

I really liked what you said about stanzas. I noticed you use couplets frequently. I think I might need to try this. for example

"lifting the veil to see

my face."

running into the next stanza, not just the next line. I see you doing this a lot. I wonder what the difference is between running into the next stanza versus running into the next line. I can see that couplets work really well in Bride, but wonder if there is any more rhyme or reason to other decisions you've made about couplets versus quatrain for example. This can be a rhetorical question!

I have also heard Stanza translated to “song,” which reminds me that both structure (room) and sound (song) are where I go when ready to revise or polish a poem.