Hi, Friend.

Today is the first birthday of For Dear Life. We’ve been newslettering together for a year! A subscriber recently called For Dear Life “a very positive and joyous space,” and that’s exactly what I was hoping for. Thank you for embarking on this creative adventure with me.

Today I’m sharing a craft tip and an in-class activity that could be tailored for a middle-school, high-school, or intro-level undergrad class.

A few days ago I posted a behind-the-scenes look at two poems written years apart. One of them, “The Hum,” relies heavily on enjambment—line breaks that don’t end with punctuation, so that the sentence continues on the next line. As I revise any poem, I weigh different line breaks and have a conversation with myself: What are the different layers of meaning I can make depending on where each line begins and ends? How does the poem sound with pauses in different places?

Each choice you make in a poem has an effect on the poem, and therefore the reader. As you try out different line breaks, ask yourself: What do I gain by breaking the line here, but what do I lose? What are the pros and cons of each choice?

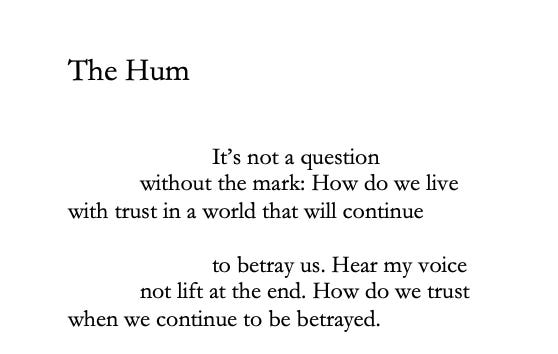

For example, here are the first two stanzas of “The Hum”:

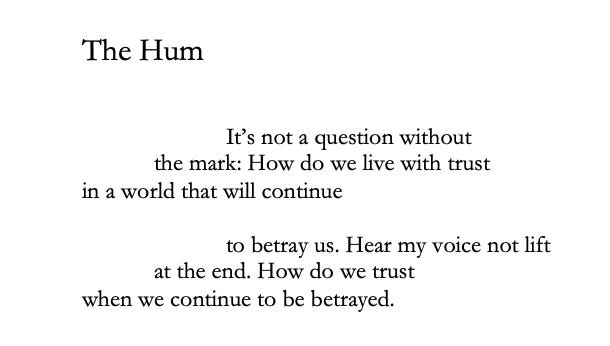

What are other options for line breaks here, and how do they change the poem? Let’s look at an example of other choices I could have made here and talk through the differences.

Here, I like the suspense and tension generated by the opening line breaking at “without” “Without what?” the reader asks herself, and must read on for the answer. I’m also drawn to “at the end. How do we trust” living together on the same line, because it reads as its own sentence.

But in the end I went with what I thought was the most compelling version. I felt “It’s not a question” was a stronger opening, and I preferred the boldness of “Hear my voice” as a command before it’s further explained, and toned down, in the next line: “not lift at the end.”

Of course all of this is subjective! There is no right answer. We experiment—try, try again—until we’re satisfied.

Teachers, as you encourage your students to play with different line breaks in their own poems, you might try this in-class activity: let them experiment on a published poem. Type up a brief published poem as a prose paragraph and hand out to students (or provide as a Google doc). Ask them to copy the poem on a new sheet of paper (or copy into a new document), breaking the lines themselves. I have used “A Small Needful Fact” by Ross Gay (a poem that is, in fact, one breathless sentence) and “I Remember the Carrots” by Ada Limón for this activity, among others.

Once students have had time to select their breaks, we share our various versions as a whole class or in small groups, depending on time and number of students, and we discuss why we made those choices and what effects we think they have on the poem—pacing, sound, tension, meaning. Finally, we look at the lineated published version together. It never fails that some students prefer their choice of lineation, or a peer’s choice, to the poet’s. The conversations we have around this activity are always really engaging.

My two cents: “First thought, best thought” isn’t a mantra I follow with line breaks. Test multiple options and weigh the pros and cons, then make the choices you think are best for the poem.

Happy writing (& revising)—

Maggie

What a fun exercise. I love that there are multiple ways that can and will work, that there is no "right" way to do line breaks, that you may end up discovering a line break that speaks to you even more than the original. I am still learning this about poetry.

I've actually done this with fifth graders. It's fascinating what they come up with (and their rationales) PLUS it totally frees them up to play with line breaks once they see that there are no rules and no one right way.